5 Secret Weapons: An Insider's Guide to Studying

- Aug 18, 2018

- 5 min read

Updated: Dec 9, 2018

You don’t go into battle without weapons.

If unarmed, even the strongest man would struggle against a sword. But with technique he may have a fighting chance, and with weapons he could win.

You cannot brute force medical school. No amount of staying up until 2am every day will save you if you don’t have the right tools, tricks and techniques.

Now that we’ve covered mindset in the previous article, it’s time to talk about the practicalities.

1. The biggest mistake medical students make is thinking we are studying when we are not.

Highlighting everything that looks like a keyword? Not studying. Reading through a textbook chapter but forgetting it a week later? Not studying. Making beautiful notes? Helpful, but not studying.

We do this because it’s been a long day, and highlighting or just reading takes less effort, and we just want to do something so we don’t feel guilty.

The thing is, it does help you understand things. But the problem is that time is limited. And reading and highlighting is more of laying the groundwork to study, not the actual studying itself. On it’s own, it’s only 20% effective.

So what is actual studying?

Testing, testing, testing.

Exams test how well you recall and analyse information. So, your brain needs to practice recalling and analysing information. Furthermore, studies show that testing is hands down the most efficient way to remember information, far more than making notes or reading.

So:

Test yourself.

Test each other – ask each other questions.

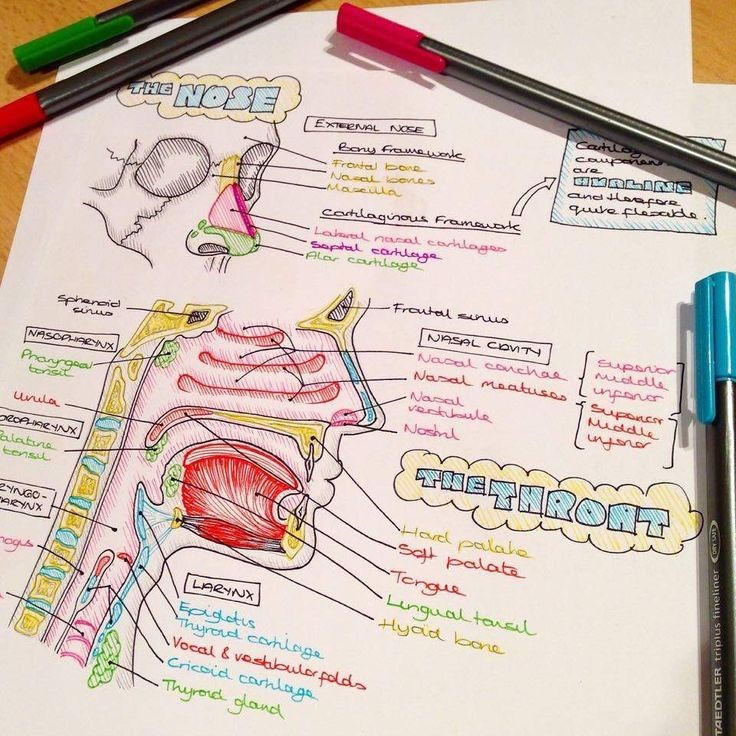

Draw out flowcharts or diagrams, or label images, without looking at the answers.

Do questions from question banks. (See here for recommendations)

Which brings me to the next point…

2. How to save a life? Flashcards.

Flashcards are easily the most efficient use of your time. Especially helpful for high-memorisation topics that require constant testing such as anatomy and pharmacology, it’s completely possible to not go to the lectures and learn purely from flashcards and still do well.

Anki is my favourite – it shows you cards at regular intervals that become longer and longer as you remember things better, and is easy to edit, include images, and share. Best of all, it has a user-friendly mobile app, which means you can study on the tube, in the bus, in between lectures, on the toilet...

Pro-tip: Ask your seniors and friends for flashcards if you don't feel the need to make your own (Pharmacology ones usually work well). Time saved not making flashcards = time better spent. Of course, if you have to make your own flashcards, go for it (just don’t spend too much time). Sometimes just googling something like ‘[insert medical school] year 1 flashcards’ will help too.

Be careful when buying commercial flashcards – they are not always aligned to your syllabus and may have more/less detail than required. Ask your seniors and friends.

P. S. Mnemonics are great, and you can incorporate them into your flashcards. You can find a huge supply online, with various degrees of humour and appropriateness.

3. How to sustain study momentum?

We’ve all had days where we study for two hours and then get so exhausted we can’t do anything for the rest of the day. The bad news is that it’s common. The good news is that it’s solvable.

What to do?

Take breaks. But not just any breaks – you don’t want to end up taking a 2-hour break for a 15-minute study session. Schedule them in advance so that you can release the mental load on your mind while not leaving breaktimes at the mercy of your mood (just ten minutes more… and five more…).

I’ve found that the most effective method is the Pomodoro (also known as the 20 min work, 5 min study) method:

Work for 20 mins.

Stop. Finish the last question and no more.

Take a break for 5 minutes.

Restart the cycle.

After 2-3 hours, give yourself a long half an hour break.

You know the rush of motivation you get when you’re doing something and have 10 minutes left? With this, you get it throughout the day, and also prevent burnout. I use 25/5 intervals instead so that I can plan my schedule in half-an-hour intervals, but whatever works for you.

There are even many apps to help with this – ClearFocus is my favorite because it sets up everything for you, and Forest lets you plant a tree with every work session you finish without using your phone!

On the topic of breaks, remember to eat well, sleep well and exercise – all of these have been shown to improve memory, energy and concentration (the endorphin release caused by exercise improves memory, for example), and cannot be neglected.

The last two tips are shorter, but still important…

4. If possible, review lectures the week they were taught.

Just make sure you understand the confusing parts – because if you don’t understand them now, by the time you revise it a few months later, you will waste time trying to understand it when you should be memorising facts instead.

However, don’t be too discouraged if it happens – to be honest, most of us spend a significant chunk of the revision period learning things we should have known a few months ago instead of revising. But the less of that, the better.

Don’t be afraid to email your lecturers – who better to ask? Sometimes they may not be helpful, but usually they are, and there’s no harm asking.

5. Prioritise, prioritise, prioritise. And don’t lose hope.

Let go of needing to know everything. You don’t have to know every single molecule or every detail of the mechanism or every side effect. Prioritise things that are high-yield, have the best effort to reward ratio, and are important for future practice.

Write plans. What you’ve done, what you haven’t, and what timeframe you have. Have just a week to the exam? Study the core content first. Ignore everything else for now. You need to schedule – assign topics to weeks, days or even two-hour intervals.

If you have friends who have finished studying a particular topic, ask them what the most important parts are. Ask what is commonly tested. Ask yourself whether it’s worth it to spend 6 hours trying to memorise one lecture. If you have to choose between two equally important things but you know you’re better at one, study that one. Focus on what you can do, not what you cannot.

As we all know, sometimes life gets in the way and your study habits are not ideal – but that’s no reason to give up, you just have to adapt to your situation.

This article may be a little dry, but I hope it has been useful!

One thing I must emphasize is that these are guidelines, not rules – while you should not let lack of familiarity with a study method stop you from trying it, in the end you should do what works best for you. Hate studying in groups? Don’t do it. Need to snack when working? Go ahead, just make the snacks healthy ones (eg. nuts or fruit) rather than crisps and chocolate. Need a 256-colour coding system for your notes? If it works for you, go for it.

And remember:

Man vs sword = stabbed.

Man + technique vs sword = in danger of being stabbed.

Man + technique + quarterstaff vs sword = still in danger… but better.

Arm yourself with tools and techniques, and you’ll survive medical school.

All the best!

By Alexis Low An Yee

Comments